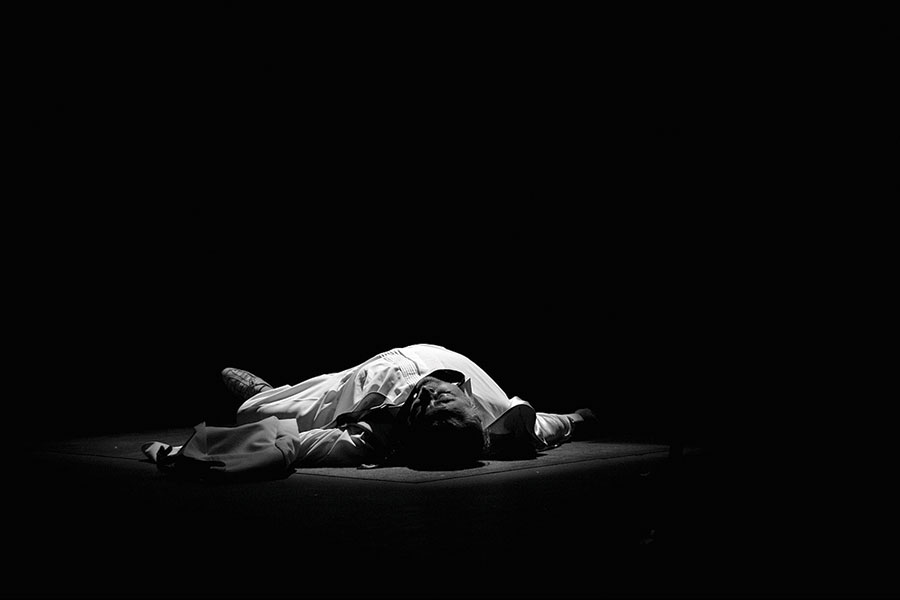

Floorlayers are among the careers in the firing line when government makes us work till we drop, writes David Strydom

TALK is rife government will soon raise the state pension age to 70. At the moment, it’s 66 and will rise to 67 by 2028, then 68 by 2046. The key phrase: at the moment. Government and those with power over our lives are itching – itching, I tell you – to push retirement age to 70 and beyond.

If they do (and were I a betting man, I’d take a big fat bet on this one), floorlayers will be one of the careers worst hit. But we’ll return to that in a bit.

First, let’s look at the scale of the problem: by 2075, there’ll be 20m in retirement because we’re all living longer, healthier lives, or so goes the theory. But that’s not strictly true. Life expectancy has slowed, just as our tax-hungry legislators are salivating at the thought of making us work till we drop.

The World Health Organisation revealed last year that Covid-19 reversed the trend of steady gain in life expectancy at birth and healthy life expectancy at birth. The pandemic effectively wiped out nearly a decade of progress in improving life expectancy in just two years.

‘Between 2019 and 2021, global life expectancy dropped by 1.8 years to 71.4 years (back to the level of 2012). Similarly, global healthy life expectancy dropped by 1.5 years to 61.9 years in 2021 (back to the level of 2012),’ said the 2024 report.

Of course, that reversal will have impacted disadvantaged communities more than western nations, but it was nonetheless a universal reversal. Don’t think for a moment, though, that governments are prepared to reduce the age of retirement on that basis. They’re still operating on the premise that age will continue rocketing upward at some point.

Except that’s not the case. The period 2021–2023 shows figures of 78.8 years for males and 82.8 years for females, an increase from 2020–2022 but still down on pre-Covid levels between 2017–2019. (In the interests of balance, it’s worth pointing out experts expect the upward trend to continue.)

And this is where the sleight of hand comes in: politicians love to quote ‘average’ life expectancy, but the lived reality for millions doesn’t reflect that neat statistic. It’s no consolation to the floorlayer with shredded joints, or the nurse on her feet for 12-hour shifts, that somewhere in a spreadsheet their peers are expected to live until 82. For people in hard physical jobs, 60 can already feel like 80.

Then there’s the fact life expectancy varies wildly between people and social backgrounds. Two of my grandparents were dead before they turned 70, and the other two didn’t much exceed that age. I’m willing to bet many readers have a similar experience.

Also, women consistently live longer than men, just check out the list of the world’s oldest people. Does that mean men should be granted their state pension earlier than women? Even a suggestion of doing so would be so inflammatory it would make Brexit look like a picnic. So, you see, all sorts of complications arise when averages are sought, and doubly so when government sticks its oar in.

The population of people at or above state pension age is projected to rise by 55% over the next five decades, increasing from 12.6m in 2025 to 19.5m by 2075, as pointed out by Tom McPhail from Hargreaves Lansdown in The Times.

As a result, spending on the state pension relative to GDP is expected to climb by more than half, rising from 5% today to about 7.7% by the early 2070s. In current terms, this equates to an additional £75bn per year. (In a widely quoted comment in The Times, McPhail goes on to suggest saving the pension by reserving it for over-75s.)

Think about that for a moment: £75bn a year isn’t pocket change. It’s roughly the size of the entire education budget, or more than double what Britain spends on defence. Imagine what could be done with that kind of money if it wasn’t locked up in pensions. You begin to see why treasury mandarins can’t stop staring at spreadsheets.

So government needs cash (when doesn’t it?), and an oft-cited complaint is increasing the numbers of people retiring and using the state pension while people are having fewer children or going childless. That means, goes the logic, workers are supporting those in retirement, and that just isn’t sustainable.

It’s a theme of government propaganda that’s used to ‘soften us up’ – if governments of every stripe continue singing the same song, we’ll become accustomed to the message and grumble less when it actually happens. Government (and more specifically the treasury) do the same thing before budgets; it’s known as ‘flying kites.’ They leak details of what they might do, which the mainstream press invariably reports on its front pages to test public opinion. Judging by the public uproar (or lack thereof), government tapers its message to avoid angering most voters. If the current government had just come out of nowhere saying it intends to increase the retirement age, there’d be howls of outrage. Granted, we wouldn’t be quite as animated as our French brethren, where protesters mean business, especially when it comes to retirement age. But we’d still be disgruntled enough to change our vote.

And don’t underestimate the power of that grumble. Politicians know pensions are a vote-killer. Tinker too much, too quickly, and you risk alienating millions of older voters who actually turn out on election day. That’s why changes are always floated in the abstract, attached to far-off dates like 2046. By the time it hits, today’s ministers will be long gone, collecting their own cushy pensions.

And that’s the point: government hasn’t mentioned an increase in retirement age ‘out of the blue.’ First, it’s legally obliged to conduct a review of pension age from time to time. And second, we’ve been successfully softened up over several governments.

Some might think this is only fair: surely the hardworking economically active shouldn’t be propping up the retired? It’s a nice sentiment, but I sincerely doubt any government really gives a damn about the ‘hardworking economically active’.

All they care about is balancing the books (at which they’ve failed miserably, by the way), and all they end up doing is taxing the hardworking until they’re grave-bound.

The more they tax us, the further back they push the retirement age, the more cash they have to blow on not very much (which is another rant altogether). And that’s the nub of the problem: we’d no doubt all be comfortable with being wrung out like an old rag if we knew our taxes were being well spent, responsibly managed and not splurged on the welfare state – or on French gendarmes.

If the state pension age is raised to 70, though, the UK wouldn’t be the first to do so: Denmark has already taken the plunge. Life expectancy in the Scandinavian nation is slightly more than the UK, so make of that what you will.

Why did Denmark decide to make its workforce work until 70? And how did the Danish react? Before we get into that, let’s look at Denmark’s system before the required age went up. Since 2006, retirement age there has been tied to life expectancy – in Denmark, that’s nearly 82. Every five years, the age was revised, and according to those laws, will rise to 68 in 2030 and 69 in 2035.

The Independent quoted a roofer telling the public broadcaster: ‘The policy is unrealistic and unreasonable. We work and work and work, but we can’t keep going.’ It might be different for those with desk jobs, he added, but workers with physically demanding jobs would struggle with the changes. ‘I’ve paid my taxes all my life. There should also be time to be with children and grandchildren.’

So not all Danes have accepted their ‘work until you drop’ fate, despite it being passed in their parliament by 81 votes for and 21 against. Interestingly, according to The Times, surveys show more than half of Danes want to keep working beyond the state pension age, gradually phasing themselves into retirement over several years during their 60s rather than cutting off entirely once they reach retirement.

That contrast is striking: while Danish workers are apparently more open to gradual retirement, Brits tend to view retirement as a cliff edge: one day you’re in work, the next you’re out. Our system has never really embraced phased withdrawal, and our work culture doesn’t make it easy either. Few employers here want someone easing down to three days a week. It’s all or nothing.

When French president Emmanuel Macron tried to increase the pension age in 2023 from 62 to 64, he met fierce, French-style resistance in the street. Anarchist factions dressed in black vandalised shops, lit trash piles ablaze, and smashed street furniture across central Paris. Riot police responded with tear gas, stun grenades, and baton charges. A bank branch, along with cars and rubbish bins, were torched as protesters escalated unrest. Protesters dumped tyres, manure, and wooden barricades to block government buildings and roads, sometimes setting them on fire, notably in Bordeaux.

A 26-year-old momentarily arrested for photographing the protests lost a testicle after being struck in the groin by a police baton. His case sparked public outrage and an inquiry.

Say what you like about the French, but they know how to make themselves heard. Pension reform there isn’t just an economic debate; it’s a cultural war over the meaning of work, leisure, and dignity in old age. Brits, by contrast, tend to mutter rather than smash things up.

And anyway, Brits may have been split on all that French ruckus. On one hand: why should the French get to retire nearly half a decade earlier than us? On the other: good for them – standing up for their right not to work until they drop!

But back to the reason for this column: those careers most affected by a change in the retirement age. According to a report in The Independent, it’s those who work in physically demanding jobs, as they could have to stay in employment longer than previously expected or retire with less income.

Those named in the report included carers, warehouse workers, tree surgeons, miners, roofers, scaffolders, fishermen, and agricultural workers, but it might just as well have mentioned floorlayers, carpet fitters, and tilers.

Don’t get me wrong: many floorlayers work to an advanced age, if their knees can take it. I’ll never forget my introduction to Keith Shenton, until lockdown, the UK’s oldest living active floorlayer.

Unfortunately, because of a dearth of industry records, we don’t know if Keith was the oldest living active floorlayer ever, but I do know the day I met him at his office on the outskirts of London, he showed off his carpet trimming skills with the vigour and ability of a 25-year-old. Astonishingly, he was 87 at the time.

That said, floorlayers face one of the toughest occupational challenges for knees in any trade, and these risks go well beyond mere discomfort. A major Danish study found being a floorlayer more than doubled the odds of developing symptomatic tibio-femoral osteoarthritis (TF OA), with an odds ratio of 2.6 compared to a reference group of graphic designers.

Clinical signs of meniscal damage were also significantly higher, with McMurray test sensitivity indicating odds over two-fold higher and joint line tenderness showing odds as much as five-fold greater in floorlayers.

These elevated risks align with broader meta-analyses: workers exposed to frequent kneeling, squatting, heavy lifting, and prolonged standing face a 52% increase in odds of developing knee osteoarthritis, floorlayers included.

Even more worrying, in this category, floorlayers are among the trades with the highest reported odds, on par with carpenters and bricklayers.

Bursitis, especially prepatellar (‘carpet-layer’s knee’), is another common ailment. Occupational studies show significantly elevated rates among floorlayers. Previous data put this prevalence at about one-third of workers in such roles.

And it’s not just knees: constant bending, twisting, and hauling rolls of carpet can wreck the back, hips, and shoulders. Many in the trade quietly leave in their fifties, not because they want to, but because their bodies simply give out. That’s the hidden human cost that never shows up in glossy pension reports.

In summary, for floorlayers, daily kneeling and twisting takes a heavy toll, substantially boosting the risk of OA, meniscal lesions, and bursitis. Over time, this can lead to chronic knee issues, reduced mobility, or even early career termination.

Sir Steve Webb, former pensions minister and now partner at LCP, warned in The Independent article that those doing heavy manual jobs are likely to struggle to keep working later in life owing to the physical toll.

He said: ‘One problem with having a single pension age for everyone is that not everyone finds it equally easy to work up to that age. Those doing heavy manual jobs are likely to struggle to keep going into their late sixties as state pension age rises and may face a gap between ending work and being able to draw a pension. This issue doesn’t just apply to traditional physical jobs but to anyone doing a particularly demanding job where they may simply be worn out by their mid-sixties or before.’

So, there you have it. We can’t say we haven’t been warned…

David Strydom is the editor at CFJ